Introduction

Sandwiched between its two giant neighbors, China and Russia, Mongolia is one of the world’s most sparsely populated nations. Despite its relatively large size—the country is only slightly smaller [2] than the state of Alaska in the United States—Mongolia is home to only about 3.2 million people. The landlocked country is a mix of steppe (grasslands), mountainous terrain (particularly in the west), and desert, notably the Gobi Desert in the south.

Internationally, impressions of contemporary Mongolia are frequently shaped by the country’s nomadic people, who have traditionally found their livelihoods in herding the “Five Jewels [3]”: sheep, goats, cattle (including yaks at times), horses, and camels (specifically the two-hump Bactrian camel [4]). All five animal types have traditionally provided Mongolians with meat, dairy products, wool, and hides. Perhaps the most iconic image of Mongolia to outsiders is the traditional nomadic home, a portable, round, wood-and-felt tent known as a [5]ger [5] (literally “home” in Mongolian), often called by the Russian word “yurt” in English.

But historically, the country is perhaps best known as the origin of the great Mongol Empire that, at its height in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, spanned much of Eurasia.1 [7] In many ways, this empire marks the start of Mongolia’s history as a unified nation, as Genghis Khan—known to Mongolians as Chinggis Khaan2 [8] (Чингис Хаан)—united the warring nomadic tribes of the Mongolian steppe and began to conquer neighboring “sedentary” civilizations. His sons and grandsons further expanded the empire, which, at its largest, stretched from Eastern Europe to Korea and from Siberia to the northern parts of the Middle East, India, and Southeast Asia, and formed the world’s largest overland empire.

Control over the greater Mongol Empire was eventually divided among Genghis Khan’s sons and grandsons, who created new dynasties, such as the Ilkhanate of Persia and the Golden Horde of Russia. Kublai Khan, perhaps Genghis Khan’s most famous successor, continued his grandfather’s conquests of the warring kingdoms of China and founded the Yuan Dynasty, reunifying what for centuries had been a divided China.

The Empire’s Fall and the Socialist Era

The subsequent history of Mongolia is much less well known. Still, this history—especially more recently—has strongly shaped the country’s contemporary education system.

After the Mongol Empire’s initial flurry of conquest and expansion, its power and influence gradually waned, especially in distant parts of the empire. There, Mongolian rulers began to adopt the customs and folkways of local communities and were eventually overthrown by native dynasties. The Mongols in the Mongolian homeland, however, continued their traditional nomadic way of life.

Still, the Mongolian homeland eventually came under the political control of the Qing, or Manchu, Dynasty of China. The country, divided administratively into Inner and Outer Mongolia, remained under effective Chinese control [9] from the late 1600s until 1911, when Mongolia declared independence under the leadership of the theocratic Buddhist leader the Bogd Khan. In 1921, with the help of the Red (Bolshevik) Russian Army, Outer Mongolia—which today comprises the modern state of Mongolia—was fully freed from the control of China and the White (Tsarist) Russian Army, which had initially entered Mongolia to push out the Chinese. Inner Mongolia remains an autonomous region within China.

Following the death of the Bogd Khan in 1924, Mongolia declared itself a socialist republic, the second in the world3 [10] after the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), which had been formed two years prior. Although never itself a Soviet republic, throughout its socialist period Mongolia remained a close ally of the USSR, with its leading party, the Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party (MPRP), looking to the USSR’s leadership in Moscow for direction and inspiration.4 [11] In return, the Soviet Union provided Mongolia with significant levels of financial support.

The Soviet Union also shaped many of the policies implemented by Mongolia during this period. Mongolia’s socialist government collectivized animal herds, often forcibly, after which herders earned a paycheck from the government but did not own their animals outright. The government also attempted to develop new industries, such as food processing and mining. Two new cities—Darkhan and Erdenet, now the second- and third-largest cities in the country, respectively—sprang up around these new industries.

Important changes also occurred at the cultural level. For one, the Cyrillic script used for the Russian language was introduced for use with the Mongolian language in 1941. Second, the Buddhist monasteries, longtime centers of learning in Mongolia, were destroyed, and many monks were defrocked and expelled or murdered.

Mass secular education also began during this period. During the Imperial Era and the subsequent years of Chinese rule, formal education was reserved for aristocrats, government bureaucrats, and Buddhist monks, and was principally conducted at Buddhist monasteries.5 [12] But Mongolia’s socialist leaders emphasized the importance of education for the masses, including girls and women. By the 1950s, the government had made the first eight years [13] of basic education—four years of elementary and four years of secondary—compulsory. Two optional additional years of secondary education followed, for a total of 10 years of basic education. The impact of these changes was impressive: During this period, Mongolia achieved nearly universal basic education and had very high literacy rates.

Mongolia opened its first university, the National University of Mongolia (NUM), in 1943. As with basic education, higher education in Mongolia closely followed the Soviet model, including the teaching of Marxism-Leninism. As many of the professors and instructors at NUM came from the Soviet Union, the Russian language established a strong foothold at the higher education level. High-achieving students were even sent to the Soviet Union and other Eastern bloc countries for more advanced education. Technical and vocational institutions also proliferated during this period.

By the mid-1980s, however, both the Soviet Union and Mongolia had begun to falter. In Mongolia, the economy had started to stagnate, and shortages frequently plagued the nation’s shops. In both countries, talk of and even early attempts at reform were growing.

Transition to Democracy and the Market Economy

In the late 1980s, young Mongolian reformers, many of whom had been educated in the Soviet Union, began to push for democratic changes in Mongolia.6 [14] Inspired by the reforms of Mikhail Gorbachev, the reformers wanted to introduce multiparty elections, which they hoped would break the MPRP’s—and the USSR’s—grip on the country. By late 1989 and early 1990, peaceful protests and hunger strikes in Sükhbaatar Square, the main square in front of the government house, had begun to multiply, attracting tens of thousands of participants.

The MPRP faced pressure from the Soviet Union to treat protestors peacefully, and both the Soviets and the Mongolian government wanted to avoid a Tiananmen Square-style confrontation. Consequently, the MPRP agreed to meet some of the protestors’ demands. As a result, Mongolia’s first multiparty elections were held in July 1990. Although the MPRP won a majority of the seats in the State Great Khural (Parliament), Mongolia still adopted a new constitution in 1992 which guaranteed all Mongolian citizens certain political freedoms and rights, including the right to an education. With these changes, the era of communism in Mongolia effectively came to an end.

But the early years of Mongolia’s transition to democracy were far from uneventful. Even before the USSR’s fall [15] in late 1991, the Soviet Union had begun to withdraw economically, politically, and militarily from Mongolia. Their withdrawal meant that Mongolia lost a major source of financial assistance and found itself in debt to Russia, the USSR’s principal successor state.

To address the financial gap, Mongolia’s government looked elsewhere, and, starting in 1990, Western and Asian donor organizations quickly began to enter the country. The largest of these were the major international financial institutions: the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the World Bank. Bilateral institutions, such as the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), also started to take an interest in Mongolia. Numerous non-governmental organizations (NGOs), such as the Open Society Foundation, Save the Children, and World Vision, established offices in Mongolia as well.7 [16] Additionally, several volunteer outfits set up operations, as did the Peace Corps [17]. The Peace Corps, which sends mostly young Americans to do volunteer work in interested countries for two or three years at a time, still sends large numbers of English teachers, in particular, to assist in Mongolian schools.

The financial institutions were especially influential, pushing Mongolia to transition to a market economy as rapidly as possible. While these institutions provide technical assistance in areas of development such as education, their support is typically contingent on their assessment of a country’s capacity to repay its loans. Therefore, as a condition of receiving these loans, Mongolia was required to accept a strict program of “shock therapy,” which paralleled similar programs adopted in Russia and other former Soviet republics [18] and Eastern bloc countries. Among the original democratic reformers, many of whom now served in the government alongside old MPRP members, opinions about these conditions were split, with many favoring a strong market economy while others were more skeptical, believing that the government still had an important role to play in the economy. Nevertheless, in desperate need of aid, the Mongolian government had little choice but to accept the conditions.

Beginning in 1991, the major donor organizations put together aid packages that included the requirement that Mongolia adopt certain “structural adjustment reforms” (SARs). These SARs included privatization of most industries and enterprises (including the herding collectives), large reductions in government budgets and spending, and removal of most price controls and import tariffs. Initially, donor aid focused on market reforms and large infrastructure projects, with little of it directed at programs to reduce poverty or support ordinary people. Although many alleged that these donor organizations simply introduced pre-packaged reforms with little or no understanding of Mongolian history and society, Mongolia’s strong dependence on aid made these organizations extremely influential within the government and society more broadly.

While the economy saw some improvements (such as restocked shops after goods shortages in the 1980s), the transition was very rocky, particularly in the 1990s. Under the guiding principle of reducing public expenditures, the government dramatically slashed spending on education, health care, and the social safety net. The animal husbandry and farming industries nearly collapsed. Poverty and unemployment were widespread. Rampant inflation and defined the early 1990s, but, luckily, the situation stabilized as the decade progressed. Outside of donor aid, the country had trouble attracting foreign investment. There were widespread accusations of bribery and corruption against government officials, and some were accused of having misused foreign aid.

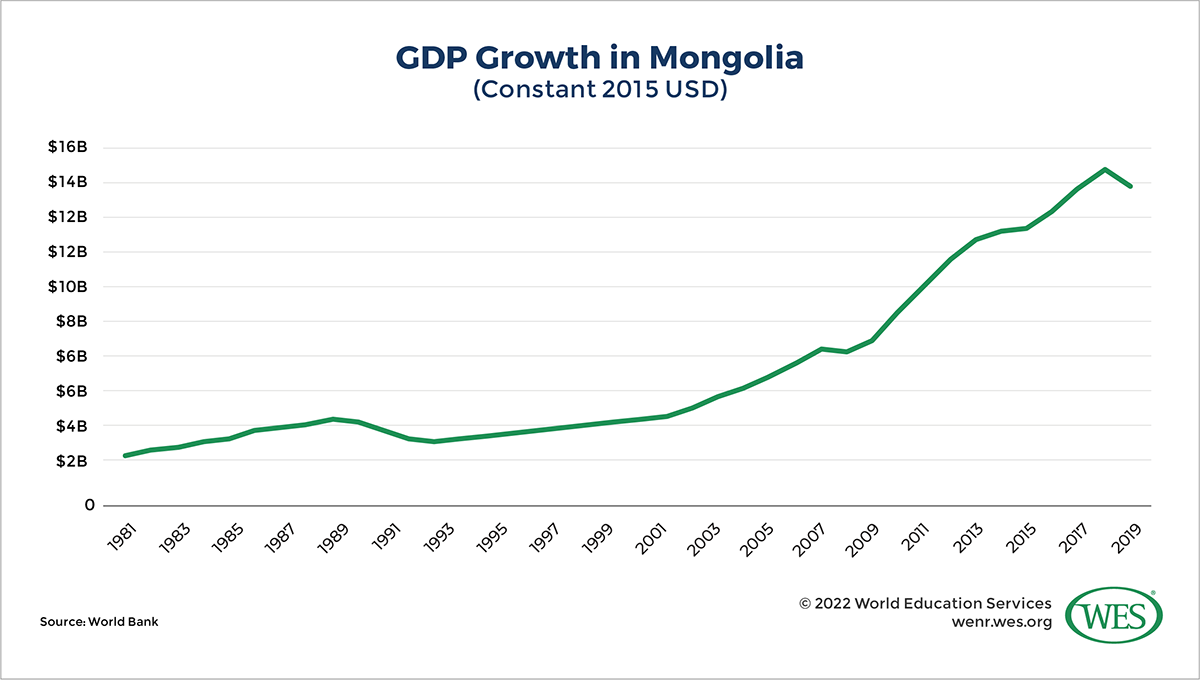

By the early 2000s, the economy had begun to stabilize and even grow. Annual gross domestic product (GDP) [19] growth increased from about 1 percent in 2000 to 10 percent in 2007. Although the country’s GDP dropped sharply in 2009 due to the global financial crisis [20], it quickly regained momentum. In 2011, Mongolia’s GDP grew at a phenomenal rate of 17 percent, among the highest [21] in the world at the time. Mining and natural resource extraction, which had focused on the country’s huge reserves of coal, copper, gold, uranium, and other minerals, were principal drivers of this growth and continue to power much of Mongolia’s economic development today.

This growth prompted the World Bank to briefly, from 2015 to 2016 [23], classify Mongolia as an upper middle-income country alongside [24] countries like Mexico, South Africa, and Turkey, as well as its two major neighbors, China and Russia. But a subsequent decline in Mongolia’s economic activity has since led the World Bank to reevaluate that assessment. Today [24], the World Bank includes Mongolia among lower middle-income countries, a classification it shares with, for example, India, Morocco, and the Philippines.

Mongolia’s growth has been accompanied by a shift in donor priorities. Following criticism from various quarters, including Mongolian government officials and even from within, donor organizations have begun to rethink their approach to aid, focusing more of their efforts on helping ordinary Mongolians.

Contemporary trends in Mongolian education have mirrored broader trends in Mongolian society. As part of the SARs, donors pushed the Mongolian government to reduce its education expenditures and introduce user fees. Many parents, particularly those from rural and nomadic communities, pulled their children out of school, as they could not afford new fees for dormitories, transportation, textbooks, and other essentials. Parents pulled boys, whose labor was needed in herding, out of school more frequently than girls, citing the curriculum’s lack of relevance for herding and a dearth of economic opportunities for school graduates.

As a result, in the early half of the 1990s, enrollment in basic education [25] decreased sharply. The gross enrollment ratio (GER) for elementary education fell from about 100 percent in 1991 to 81 percent in 1993. Over the same period, the lower secondary GER fell from 91 percent to 76 percent, and upper secondary GER fell from 69 percent to 45 percent. A 2010 policy note from the attributed the marked decline to the “contraction of fiscal and household expenditures and […] the dismantling of the collectives and social safety nets which provided [basic educational] services.” The initial post-socialist years also saw many schools close because of a lack of funding and teachers, large numbers of whom quit due to poor salaries and a lack of teaching resources.

In the late 1990s, however, enrollment began to recover. By 2000, elementary enrollment was near universal, and secondary enrollment returned to levels close to those of 1990.

In large part due to the demand for skilled labor in the market economy, Mongolian higher education expanded very rapidly [26] during this period. In 1991, the higher education GER was only about 14 percent, but by 2009, it was 47 percent. The number of higher education institutions also proliferated. Over the same period (from 1991 to 2009), the number of public institutions increased from 14 to 42. Even more notable was the growth of private institutions, which did not exist during the socialist period. By 2009, there were 151 such institutions, though most of them were very small.

Since the 1990s, Mongolian education at all levels has relied heavily on aid and technical assistance from donor organizations. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) has been particularly active in education, often as an advisor to the education ministry.8 [27] Other organizations, including the World Bank, bilateral organizations, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), have carved out niches for themselves when it comes to aiding Mongolia’s education system. This assistance has typically been designed and marketed as a way to improve Mongolia’s economy. The government has introduced various reforms, often first developed in Western countries, such as student-centered learning, outcomes-based education, and even vouchers. One important reform occurred in the 2000s when Mongolia moved from a 10-year basic education system modeled after that of the Soviet Union, to the more internationally standard 12-year model (described in more detail below).

Education During the COVID-19 Pandemic

As was the case worldwide, the COVID-19 pandemic caused major disruptions to education in Mongolia. The government decided to shift education throughout the country online starting in January 2020. Online education is new for Mongolian teachers and students, especially at the secondary level, so almost all schools have held trainings to instruct teachers and students in how to organize and attend online courses. Students at all levels, from early childhood education to higher education, started online courses using a variety of different platforms. For younger students, particularly those at the kindergarten and elementary levels, lessons were broadcast via television [28] nationwide. At the secondary and higher education levels, various modes have been used, from television to online platforms such as Moodle, Google Classroom, and Zoom. Most in-person learning resumed [29] in fall 2021, with most students following a hybrid schedule [30] that combines in-person and virtual classes.

An Overview of Mongolia Today

Geography and Climate

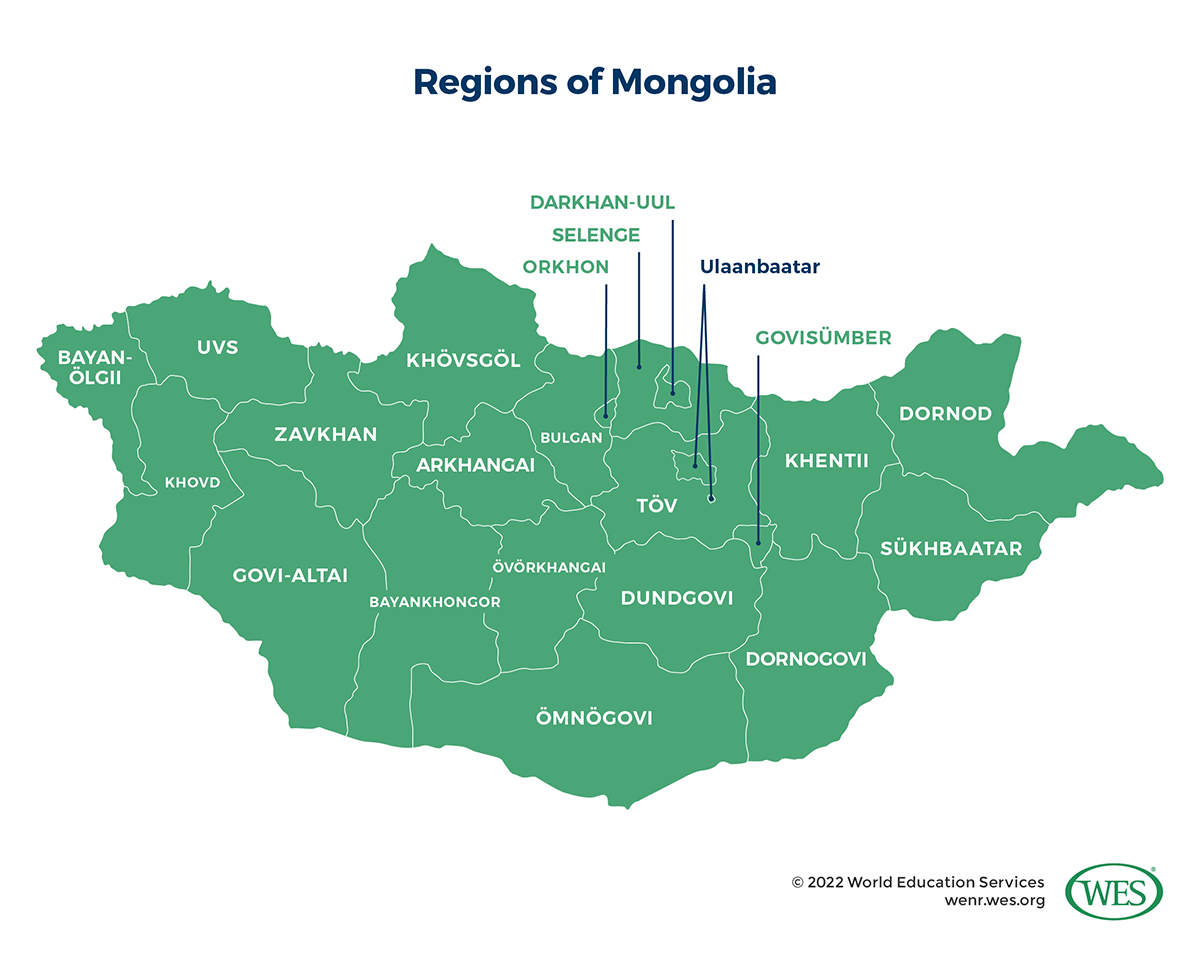

Mongolia is composed of 21 provinces each called an aimag (аймаг) and the separately administered city (khot or hot/хот) of Ulaanbaatar (Улаанбаатар),9 [31] the national capital and home to about 45 percent of the total population [2]. Each aimag has a capital known as an aimag center (amgiin tüv/амгийн төв) and is further divided into administrative units, each called a soum (сум; sometimes sum in the Latin script). Soums are composed of a soum center (generally a village that serves as the administrative center of the soum) and smaller geographic units each called a bag (баг), the smallest administrative unit in Mongolia outside of the capital. Ulaanbaatar is composed of districts, each called a düüreg (дүүрэг) and further subdivisions, each called a khoroo (хороо).

Mongolia has an “extreme continental climate” [13] and is known for its freezing winters. About half of the ground across the country is permafrost. The climate is also semi-arid. Mongolia is susceptible to drought and to particularly harsh winters known as dzuds, in which herding animals are known to drop dead in the freezing temperatures. These issues, which climate change will likely exacerbate, have caused significant dislocation among the country’s traditional nomadic population, forcing many to migrate [33] to Ulaanbaatar and other large cities.

Government

Mongolia is a parliamentary democracy. The current constitution was ratified [35] in 1992 and amended in 1999 and 2001. The legislative branch is the Parliament, or State Great Khural (Ulsyn Ikh Khural). The 76 ministers in the unicameral10 [36] State Great Khural serve four-year terms. Executive power rests largely with the prime minister and the cabinet, which are charged with executing the country’s laws, mainly through numerous ministries. The head of state, however, is the president, who is elected by the people from among nominees selected by every political party with at least one seat in the State Great Khural. Although the role is largely ceremonial [37], the president does serve [38] as the commander-in-chief of the armed forces and has the power to veto legislation, appoint judges and ambassadors, and negotiate international treaties. The judicial branch [37] is headed by the Supreme Court, whose judges are appointed for lifetime terms.

At the aimag level [39], the prime minister appoints the governor, who serves alongside a local assembly (khural) elected by the people every four years. Aimag governments have their own administrative apparatus and budget. In the city of Ulaanbaatar, the executive leader is a governor-mayor. Each smaller unit [23]—soum, bag, and district and khoroo of Ulaanbaatar—has a governor and khural as well.

Governments in Mongolia change frequently [23]. From 2000 to 2014, there were 16 changes of government. As a result, educational policies change often as well.

People and Language

Mongolia is made up predominantly of ethnic Mongols, the largest percentage of whom are Khalkh Mongols. All the various sub-ethnic groups of Mongols speak highly related variations of the Mongolian language.

Mongolian is also the official language of the country. The Mongolian language is usually classified [40] as a subfamily of the Altaic language family, though this classification remains controversial and is not universally accepted. In this typology, Mongolian is divided into eastern and western branches spread across greater Mongolia, which includes swaths of China (notably the regions of Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang) and the Russian Federation. Some related languages exist further afield, notably the Moghal language of Afghanistan and several languages spoken in parts of western China. The language family shares similarities [41] with the Turkic languages of Central Asia. It is unrelated to Chinese and other tonal languages, although it contains a significant number of loan words from Chinese and Tibetan.

In reality, the Mongolian language (Mongol khel/Монгол хэл) is a collection of highly related [41] languages and dialects. In Mongolia, the government considers Khalkh Mongolian, the most-used variation of Mongolian, the country’s official language.

The country’s largest minority groups are Kazakhs and Tuvans,11 [42] whose languages are Turkic in origin [43]. Kazakhs are most heavily concentrated [44] in the far western aimag of Bayan-Ölgii and to a lesser extent in Khovd aimag (also in the west of the country), as well as in Ulaanbaatar. Kazakh is the dominant language in Bayan-Ölgii, though Mongolian is the main language of communication [45] between Mongolians and other ethnic groups.

The traditional Mongol script [41] and alphabet were developed from the Uighur alphabet during the imperial era. This script is written top to bottom and left to right. During the socialist era, however, the Republic of Mongolia adopted the Cyrillic script used for Russian and some other Slavic languages. The Mongolian alphabet in Cyrillic uses the 33 letters of the Russian alphabet, plus two additional vowels—ө and ү.

Today, the Cyrillic script is used for most day-to-day activities, although the traditional script is still used for some purposes, such as for formal documents and occasions, and students learn both scripts in school.12 [46] However, in March 2020 [47], the Mongolian government announced that the traditional script would become the nation’s official script by 2025. The decision is not expected to completely supplant Cyrillic, which will likely continue to be used for many day-to-day activities.

Conventions governing the transliteration of Mongolian into the Latin script, particularly for online purposes, have yet to be standardized. For casual activities, such as text messaging (SMS) and posting on social media, many Mongolians use the basic Latin alphabet [48] (the same as the English alphabet), despite its inability to transliterate some Mongolian vowels well. Others utilize the German umlaut [49] to transliterate certain vowels, notably ö for the Mongolian letter ө and ü for ү. In this profile, an expanded Latin script that includes the umlaut is used to transliterate Mongolian words.13 [50]

Mongolian Names and Titles

Mongolians generally go only by their first (given) name. They do not have surnames or family names as in other parts of the world. Instead, for official purposes, they may use their father’s given name, often placed in front of their own name in possessive form. In most cases, they use an abbreviated form of their father’s given name, placing just the first letter of their father’s name in front of their own name.14 [51]

However, beginning in the late 1990s [52], the government began a push to give everyone surnames [53] as part of a modernization effort. Initially, the government preferred that citizens find their old clan or family names, which had been prohibited during the socialist period,15 [7] but many Mongolians ended up submitting a Mongolian word as their new surname. Today, however, most Mongolians only use this surname for official purposes, such as on their government ID cards.16 [54] Historically, Mongolians had clan names, dating back to imperial times. However, the socialist government of Mongolian banned these names for a variety of reasons.

Mongolians generally do not use titles equivalent to “Mr.” or “Mrs.” in English, except for some formal ceremonies. It is common, however, to refer to an individual by their profession, particularly in professions of high standing such as doctors and teachers. Mongolian students usually call teachers, professors, and lecturers “Teacher” (bagsh (багш); bagshaa (Багшаа), in direct address) or use the teacher’s given name followed by the title “Teacher” (for example, Narantuya Teacher, or Narantuya Bagshaa).

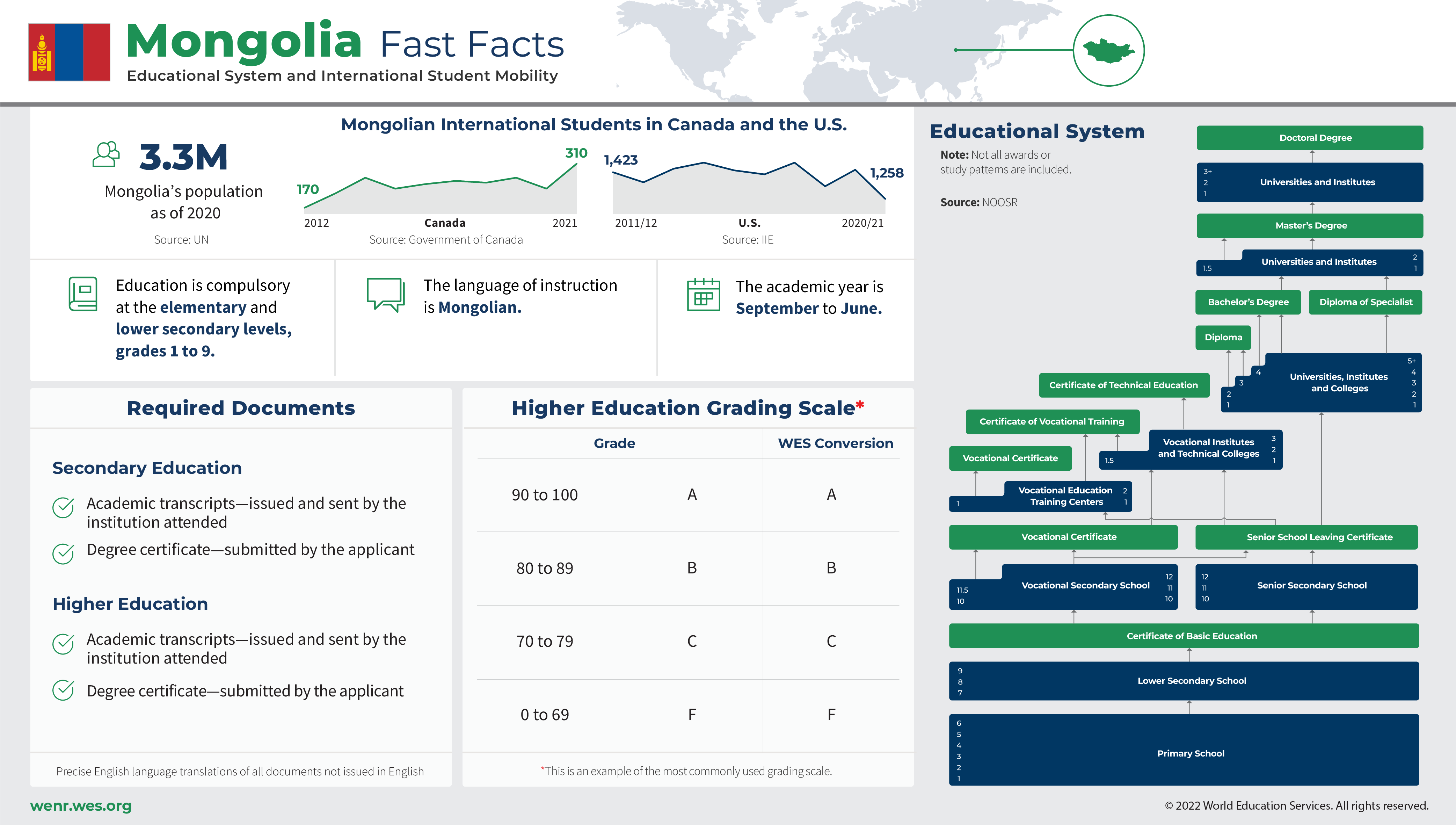

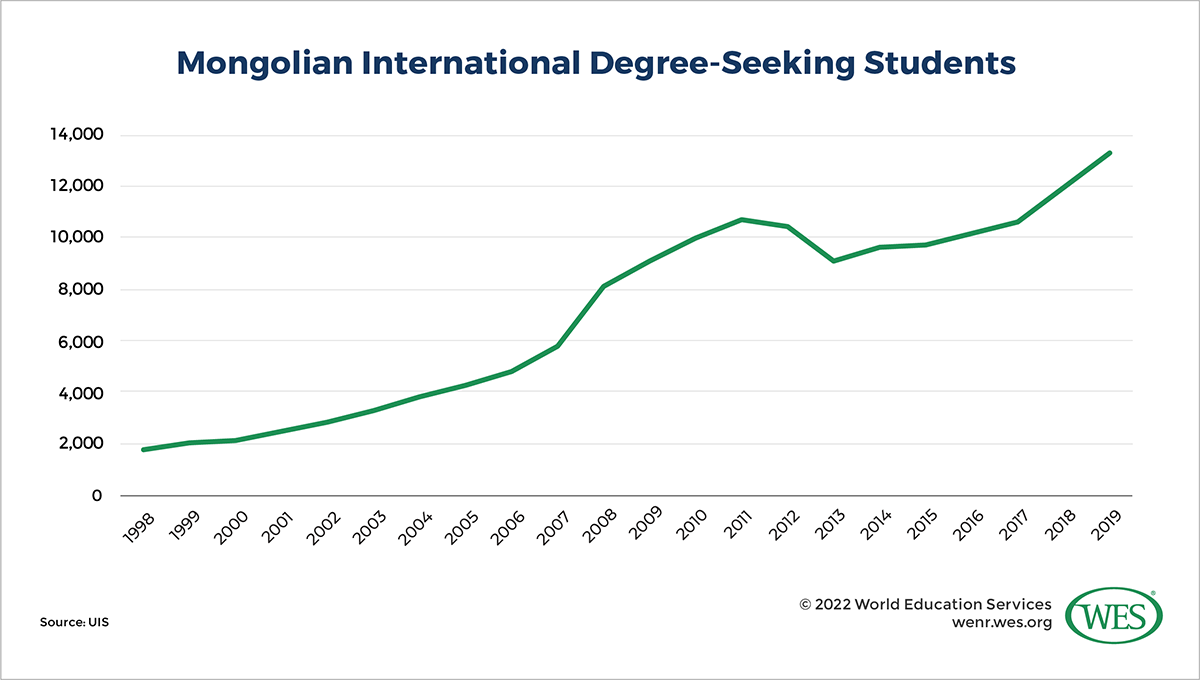

Outbound Mobility

UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics (UIS) estimates [55] that about 13,330 Mongolian students were studying abroad in 2019, up from 9,610 in 2014. However, due mostly to a lack of Chinese data in UNESCO’s reporting, these numbers are likely a significant underestimate of Mongolia’s actual outbound student mobility.

Prior to the 1990s, most internationally mobile Mongolians studied in the Soviet Union and Soviet satellite states [26]. Today, however, neighboring Asian countries attract the largest numbers of Mongolian students, followed by several major Anglophone countries. It is likely that the largest number of students are studying in China.17 [56] According to China’s Ministry of Education [57], 10,158 Mongolian students were studying in China in 2018. According to UIS data, after China, the countries hosting the largest cohorts of Mongolian students are, in descending order: South Korea, Japan, the U.S., Australia, and the Russian Federation.

The Mongolian government provides loans [59] to many students going abroad through the Education Loan Fund, which requires students to return to and work in Mongolia for at least five years after they’ve completed their studies. Students who study abroad can also earn a government grant [60] which helps cover tuition fees and some living expenses.

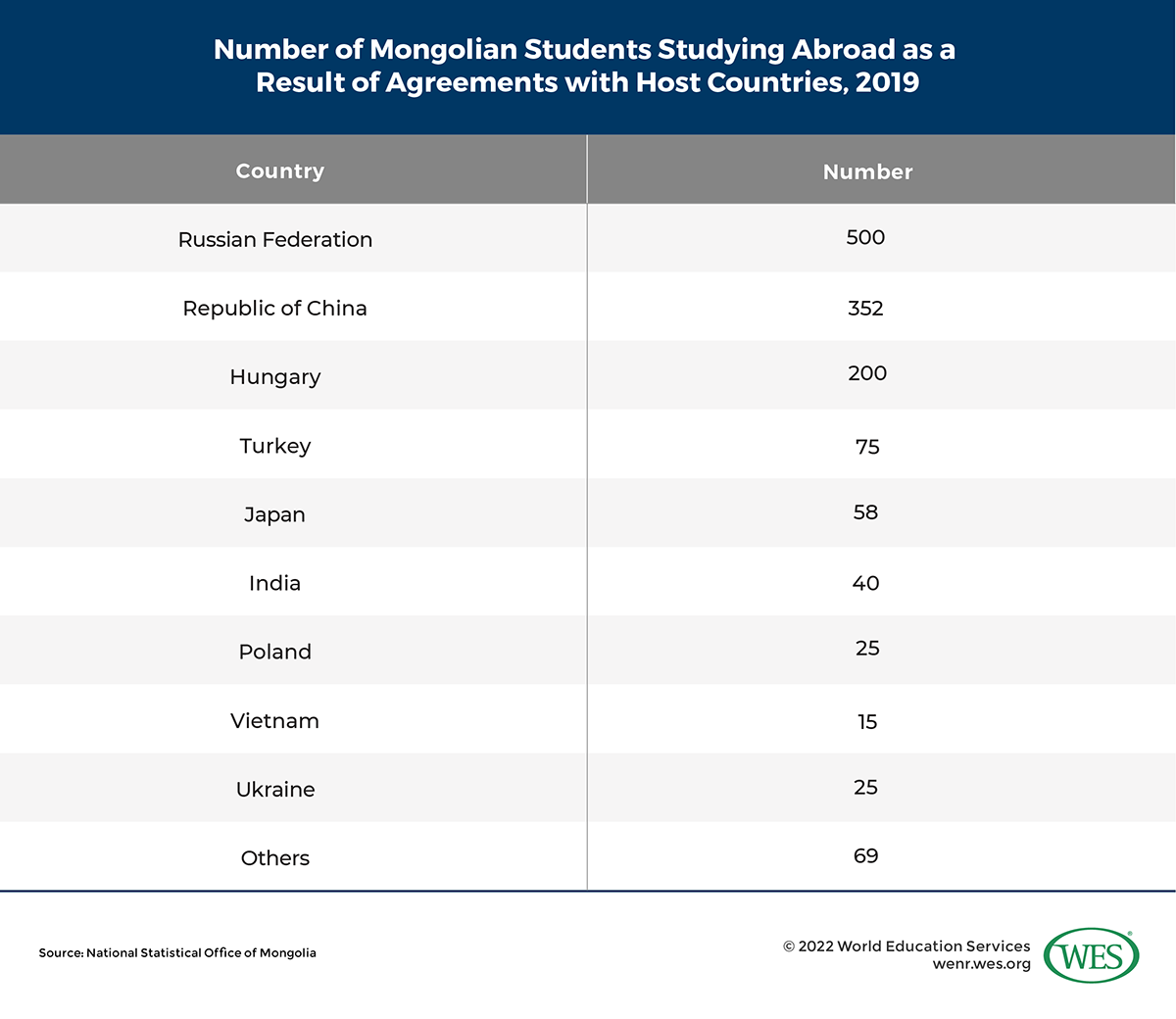

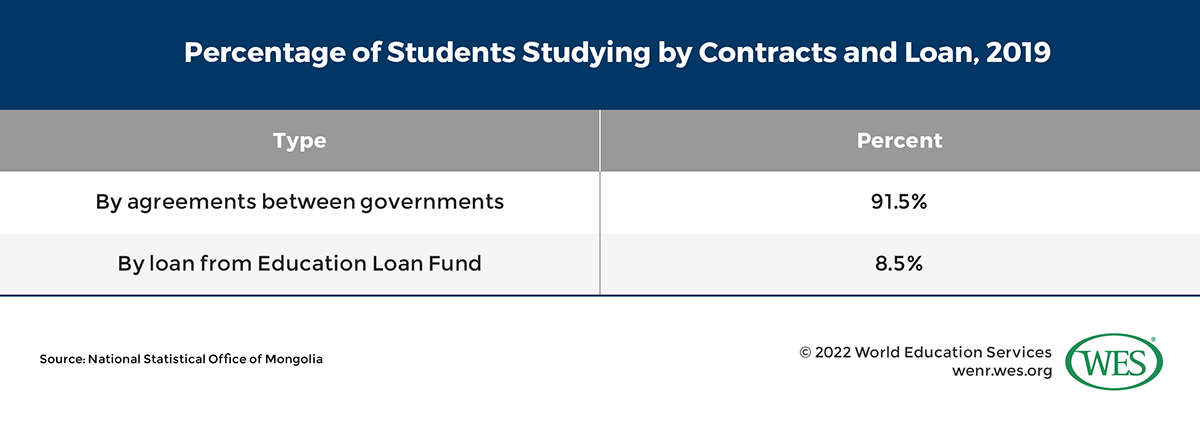

Some Mongolian students study abroad on scholarships funded by host country governments or institutions. According to the Mongolian government [61], in 2019, 1,500 Mongolian students enrolled in institutions in other countries based on agreements between the Mongolian and host country governments. These agreements range from bilateral scholarships that reduce tuition fees for Mongolian students, to pathways that open opportunities for Mongolian students to study in specific countries and institutions. The top destination countries with such agreements are Russia, China, and Hungary. According to the Mongolian Ministry of Education and Science (MES), in 2020, 92 percent [62] of Mongolian students studying abroad were enrolled in countries where agreements between the Mongolian and host country governments were in place; 9 percent of these students received financing from the Education Loan Fund.

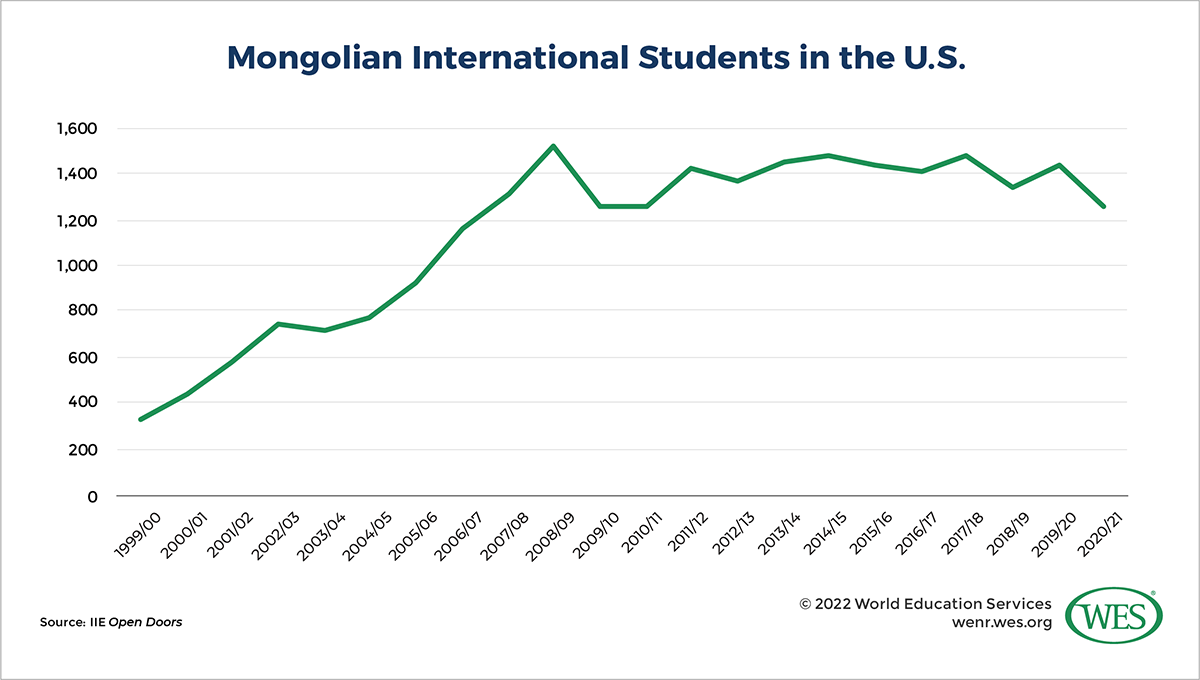

United States

In the 2019/20 academic year, 1,438 Mongolian students studied in the U.S., according to IIE’s Open Doors [65]. In 2020/21, this number decreased 13 percent to 1,258, almost certainly due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused the total number of international students in the U.S. to decrease [66] by 15 percent. Still, even in the years prior to the pandemic, the overall number of Mongolian students in the U.S. fluctuated. At this point, the future of Mongolian student enrollment in the U.S. is unclear.

In 2019/20 [67] , the academic year that ended with the start of the pandemic, the largest number of Mongolian students in the U.S. were by far undergraduates—834, or nearly 60 percent. Graduate students totaled 272. There were 107 Mongolian students in non-degree programs, which would include short-term study abroad students, those working on certificates, and those attending non-degree English programs, often with the intention of matriculating into a degree program. There were also 225 Mongolian students on optional practical training, or OPT [68]. In 2020/21, well into the pandemic, there were declines at all levels, with non-degree students and OPT students responsible for the largest declines, mirroring overall international student trends.

Mongolia is the fifth-highest sender of international students to the state of Alaska, behind Canada, China, South Korea, and India. In 2020/21, Mongolians made up around 5 percent of the total international student population in that state. In the years prior to the pandemic, they made up an even greater proportion of Alaska’s international student population.

There are some striking similarities between Mongolia and Alaska, notably the climate, rugged geography, and sparse population. There also appears to be some cooperation [70] between the two regions as well, particularly between Mongolia’s Armed Forces and the Alaska National Guard. As of 2017, there is a formal partnership [71] between the National University of Mongolia (NUM) and the University of Alaska Anchorage (UAA). Such partnerships may help facilitate the mobility of Mongolian students to the state.

The Mongolian government has tried to develop partnerships with U.S. universities and colleges and negotiate discounted tuition for Mongolian students. In early 2021, the Minister of Education and Science, L. Enkh-Amgalan, discussed the ministry’s negotiations with U.S. stakeholders regarding reducing tuition costs for Mongolian students who wanted to study in the U.S. to a rate similar to what in-state domestic students pay at public universities. He was quoted as saying, “Our undergraduate and master’s level students in the U.S. pay the average tuition fee at minimum US$30,000 to 40,000. We will try to negotiate contracts with U.S. governments [72] to decrease tuition to the U.S. domestic rate of $5,000 to $10,000. Currently, two to three states in the U.S. have said they will accept our offer.”

As one example, the Mongolian MES and the University of Missouri—Kansas City (UMKC) signed a memorandum of understanding [73] on March 19, 2020. For Mongolian students enrolling in UMKC’s bachelor’s and master’s degree business programs, the agreement sets tuition and other fees at levels similar to what in-state domestic students pay. Engineering and science students can also study at a discounted tuition rate of $8,500. Tuition fees for out-of-state domestic and international students at UMKC are currently about $24,000 a year. For Mongolian students, the rate is now $9,900. There are also plans to develop a dual degree program with the Mongolian National University of Medical Sciences.

Similarly, the Science and Technology University in Ulaanbaatar and George Mason University in Virginia [74] signed a memorandum on March 11, 2021. According to this contract, the two institutions will implement a 2+2 dual degree program that offers Mongolian students some financial support. Ordinarily, international students at George Mason pay $26,000 in tuition each year. By contrast, Mongolian students will be awarded grants of $5,000 and could receive further discounted tuition.

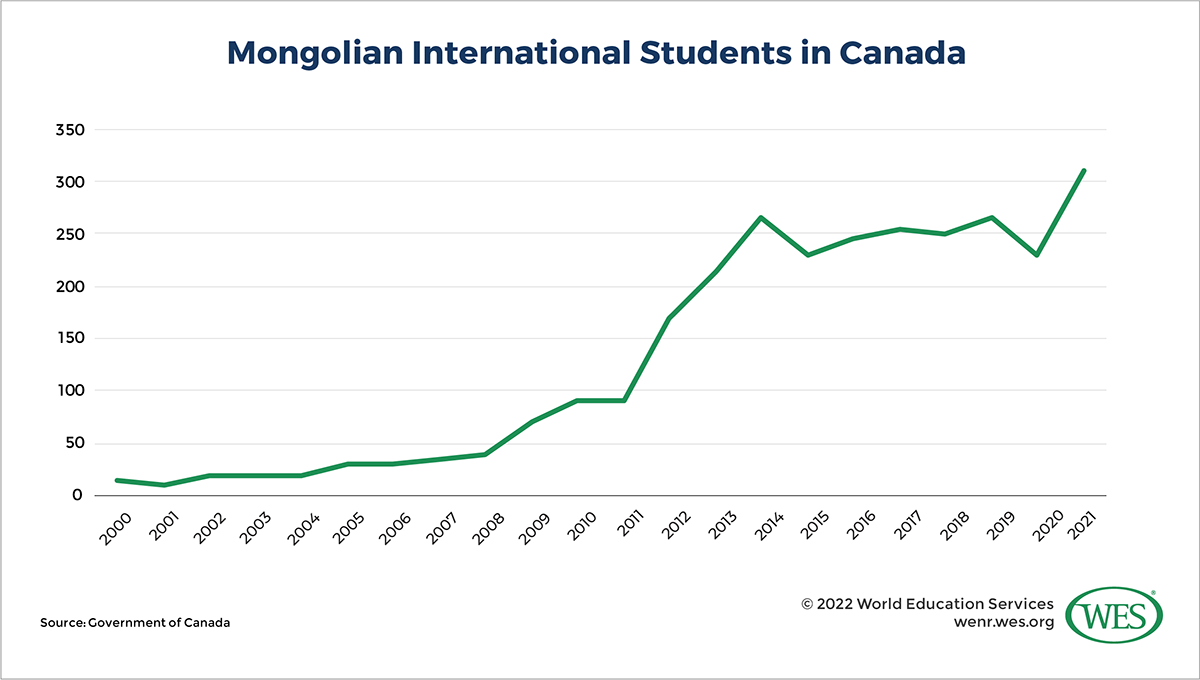

Canada

Canada is not a significant destination for Mongolian students. In 2019, prior to the pandemic, there were 265 Mongolian students studying in Canada at all levels (including K-12), according to Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) [75] data. This number dropped to 230 in 2020, after the pandemic started. Despite the relatively small numbers, there has been a significant percentage growth in Mongolian students in Canada. For example, in 2004, there were only 20 Mongolian students in the country. From 2011 to 2012, the number almost doubled, from 90 students to 170. So there is potential for future growth of the number of Mongolians in the country.

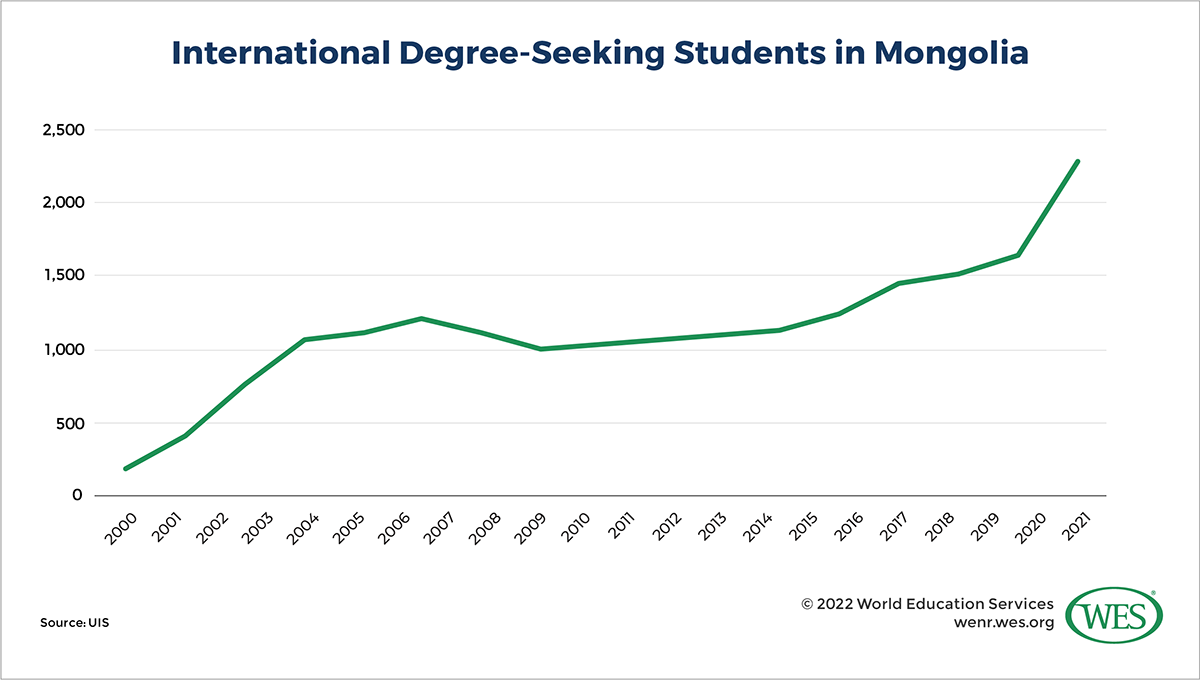

Inbound Mobility

In absolute numbers, Mongolia is not a significant study destination for students from other countries [55]. The inbound mobility ratio (that is, the percentage of students from other countries out of Mongolia’s total student population) is 1.4 percent. There are a little over 1,600 students from China, and while there is a dearth of available data, it’s possible that a significant number are ethnic Mongols coming from Inner Mongolia, a semi-autonomous region in China just across the border. There are a few hundred students each from Russia and South Korea. One major barrier for students from other countries is likely the use of the Mongolian language as the medium of instruction for the majority of academic programs. There are only an estimated seven million speakers [77]of the language, most of whom live in Mongolia or China.

According to IIE’s Open Doors data on U.S. study abroad students [79], there were 31 American students on short-term educational exchanges in Mongolia in the 2019/20 school year (the school year that ended with the start of the COVID-19 pandemic). The number peaked the previous academic year at 132 students. For at least the previous 10 years, the number of U.S. study abroad students in Mongolia had fluctuated tremendously but had never exceeded 100.

Transnational Education

Two Russian state universities operate in Mongolia and are accredited [80] by the Mongolian National Commission of Education Accreditation (MNCEA): the Ulan Bator Institute of G.V. Plekhanov Russian University of Economics [81] (PRUE) and the Ulaanbaatar branch campus of Irkutsk State Transport University [82] (IrGUPS, the acronym in Russian). PRUE offers university degrees at all levels, and all instruction is conducted in Russian. IrGUPS focuses specifically on railway technologies, though it awards degrees in a variety of technical and vocational fields [83] at the post-secondary and higher education levels as well.

The German-Mongolian Institute for Resources and Technology (GMIT) [84] was founded in 2013 in Ulaanbaatar as a partnership agreement between the Mongolian and German governments. The governing body [85] of the institution is composed of representatives from both governments. The institution, however, is accredited [86] as a public Mongolian institution. It provides bachelor’s and master’s degrees in various engineering, mathematics, and natural sciences disciplines. The language of instruction is English.

Administration of the Education System

The Constitution of Mongolia, adopted in 1992, guarantees all citizens a free basic education.15 [87] Education in Mongolia is further governed by the Education Law and several subsector laws, such as the Preschool Education Law and the Higher Education Law.

The top authority for education within Mongolia is the Ministry of Education and Science [88] (MES) (or Bolovsrol, Shinjlekh Ukhaany Yam/Боловсрол, Шинжлэх Ухааны Яам).16 [89] MES is responsible for:

- Developing and executing national education policy

- Developing standards of education at all levels

- Developing curricula

- Creating and publishing textbooks

- Overseeing teacher training

- Determining the school year

- Developing and administering national examinations

- Accrediting higher education institutions

- Licensing new higher education institutions

- Overseeing educational research17 [90]

MES is led by the Minister of Education, a parliamentarian installed by each new government in charge in the State Great Khural (Parliament). As mentioned, governments change frequently [13], and from 2016 to 2020, there were four different education ministers. As a result of frequent turnover in the ministry, policies can change rapidly.

The Ministry is divided into numerous departments [91], notably the Department of Preschool Education, the Department of Primary and Secondary Education, and the Department of Higher Education.

Technical and vocational education and training (TVET) is jointly administered [92] by the MES and the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection (see the TVET section).

Local governments are in charge of education within their jurisdictions, and are responsible for administering and managing formal and non-formal education and in-service teacher training.18 [93] Each aimag also has an office of education responsible for overseeing schools [92] and improving performance.

Local political officials also appoint the heads of individual schools [94], who are typically called a zakhiral (захирал)—or director, in English. There appear to be no particular qualifications required of school directors.

Education Reforms

Since the 1990s, the most significant educational reform [95] in Mongolia has been the gradual transition from a 10-year system of education to a 12-year system more in line with international standards. Through changes to the Education Law, the new system was rolled out in stages, with the 10-year system transitioning to an 11-year system in 2004 and then to a 12-year system in 2008. As UNESCO notes [13], “The first cohort of students to have completed the full 12-year cycle [graduated] in 2020.”

Academic Calendar and Language of Instruction

The academic year runs from September to June [96] and lasts 32 weeks for elementary school students and 33 weeks for secondary school students. During the school year, there are typically significant breaks for the New Year, the Lunar New Year (called Tsagaan Sar in Mongolian),19 [97] and in the early spring.

Mongolian—specifically Kalkh Mongolian (see the Mongolian Language section)—is the official language [98]of the country and the main language of instruction. However, Kazakhs have the right to learn in their own language while also being instructed in the Mongolian language. There are both Kazakh- and Mongolian-medium schools in Bayan-Ölgii aimag [44], where the Kazakh minority is most heavily concentrated. Observers have identified issues with second language acquisition [99] of Mongolian among Kazakh children. Some Mongolian Kazakhs, particularly from Bayan-Ölgii aimag [100], go to Kazakhstan to study at the university level.

Early Childhood Education

Early childhood education (ECE) in Mongolia is typically referred to as “kindergarten” (tsetserleg/цэцэрлэг, literally “garden” and “kindergarten”). It is available but not mandatory for children ages 2 [13] to 5 [13], and it is largely funded by the government.21 [101] While access has improved nationwide,22 [102] access for the children of herders in rural areas remains an issue,23 [103] as does access for disabled and poorer children [59] in major cities, particularly Ulaanbaatar. Many rural families live far from the soum centers where the preschools are located and lack access to transportation.

Basic Education

Basic education—1st through 12th grades—is freely available to all Mongolian children under the national constitution. It is compulsory until the end of ninth grade. Elementary and secondary schools are generally available in each district [104] (soum in the aimags or duureg in Ulaanbaatar). Typically, all 12 grades of basic education are offered at one school.24 [105] However, in some rural areas, there may be only an elementary school or a combination elementary-lower secondary school, after which students must go to the aimag center or Ulaanbaatar to attend secondary or upper-secondary school.

Schools usually consist of just one building, where students of all levels study. Schools where separate levels (elementary, lower secondary, and upper secondary) are housed in different buildings on the same campus are often called complex schools.

In the 2019/20 school year, out of a total of 802 schools [106], there were 79 elementary-only schools (grades 1–5), 115 combination elementary-lower secondary schools (grades 1–9), 563 schools housing all grades (grades 1–12), and 45 complex schools (grades 1–12). Eighteen percent [59] of schools are private, and 245 are located in Ulaanbaatar. The private school sector is growing quickly, particularly in Ulaanbaatar, although these schools tend to enroll significantly fewer students than do public schools.

Enrollment Trends

Enrollment in basic education dropped precipitously in the 1990s. In 1987, for example, the net enrollment ratio [107] (NER) for elementary education was 95 percent. In 1995, it was 81 percent. However, the government has made concerted efforts [59] to increase enrollment, and in recent years, both gross and net enrollment ratios have been very high [59]. In 2015, the elementary NER was 96 percent, with 94 percent of graduates continuing on to lower secondary education. By 2018, the elementary NER [107] had risen to 98 percent. For secondary education, the NER grew from 59 percent in 1995 to 82 percent in 2006.

On the other hand, children from low-income Mongolian families, in both rural and urban areas, continue to face difficulties [59] that can prevent them from accessing elementary and secondary education. There are also major gaps in access among traditionally disadvantaged groups at all levels. These include disabled children, children in rural areas, children from poor, farming, or herding families, and members of minority groups, notably Kazakhs and Tuvans. One major access issue in urban areas is the distance between home and school for many of the poorest children, particularly in Ulaanbaatar, where the most recent migrants live on the outskirts of the city. While transportation is often provided, parents typically need to pay for it. Many of the poorest families cannot afford this service.

Curriculum Development

From 2012 to 2018, the Mongolian Institute for Educational Research [108] was responsible for developing the curriculum for all core subjects.

In 2019, MES revised [62] the preschool, elementary, and secondary education curricula in collaboration with key government agencies, teachers, and researchers. All schools started teaching the fully revised curriculum in the 2019/20 school year. The revision aimed to eliminate duplicate content, to ensure continuity from one grade to the next, to appropriately calibrate the difficulty of different subjects, to reduce the number of learning standards and objectives, and to align learning objectives with good theoretical and methodological practices.

Standardized Testing

Mongolian students are required to pass national examinations [109] to matriculate out of elementary and lower secondary school and to graduate from upper secondary school. In all other years and beginning in the third grade, students take exams designed to assess their level of knowledge and skills and inform the implementation of the curriculum.

In 2021 [110], for the first time, Mongolian students took [111] PISA, the Programme for International Student Assessment, organized by the OECD [112] (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development). Conducted every three years, this multinational examination tests the reading, mathematics, and science skills of 15-year-olds. As of early 2022, data from the 2021 examination were not available.

In 2007, Mongolia participated in TIMSS [113], the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study, from developed by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement [114] (IEA) and administered by Boston College [115] in the U.S. The country has not participated [116] since, and no data from that exam are publicly available for Mongolia.

Elementary Education

Mongolian children start elementary education (baga bolovsrol/бага боловсрол) at the age of six.25 [117] Elementary education lasts from first until fifth grade. Students usually have one main teacher [118] who teaches core subjects such as civics, mathematics, the Mongolian language, science focused on nature and the environment, and social studies. Students begin studying English in fifth grade. Separate teachers may teach special subjects such as art, the English language, health education, music, physical education, and technology. Instruction per subject lasts 35 minutes for first and second grade students and 40 minutes for third through fifth grade students. As noted above, the school year at the elementary level lasts 32 weeks.

In first and second grades, students are evaluated only through formative assessments [119]. Beginning in third grade, teachers assess students using written and oral exams at the end of both semesters. The end-of-year assessment determines the student’s final grade for the year. Students are given both percentage and numeric final grades. At the end of fifth grade, in order to matriculate to lower secondary school, students must pass the National Primary Examination [109], which covers three subjects: mathematics, Mongolian language, and science. There is no formal exit qualification awarded to students at the end of elementary school.26 [120]

Lower Secondary Education

Lower secondary education (dund bolovsrol/дунд боловсрол) lasts from sixth through ninth grade, when students are usually about 11 to 14 years old.27 [121] Students have one homeroom teacher and separate teachers for each subject. Students stay in the same classroom, and the teachers come to them.

The curriculum [118] includes computer science, design and technology, English, fine arts (art and music), health education, literature, mathematics, Mongolian language, Mongolian script, physical education, Russian, science (physics, chemistry, and biology), and social science (civics, geography, history, and social studies). Many schools offer special programs for gifted students; there are a few separate schools for such students.28 [122]

Each class lasts 40 minutes [118] and the school year is 33 weeks [123]. Some schools utilize a shift system because of overcrowding. At this age, students often first become involved in extracurricular activities such as art, technology, and various clubs focused on skills and hobbies such as chess, dance, clothing design, knitting or sewing, and music. Some after-school activities are designed to help students who have fallen behind catch up.

To matriculate to upper secondary education, students must pass the Basic National Examination [109], which tests the students in four areas:

- Mongolian language (including the traditional script) and literature

- Mathematics

- Choice of one of the following: history, science, or social studies

- Choice of one foreign language: English or Russian

Upper Secondary Education

Students attend upper secondary education from 10th to 12th grade and study the following compulsory courses [118]: biology, chemistry, computer science, design and technology, English language, geography, health education, literature, mathematics, Mongolian language, Mongolian script, physical education, physics, and social studies. Students take four elective courses in the 10th grade and three each in the 11th and 12th grades. Instruction per subject typically lasts 40 minutes.

Elective courses [118] in upper secondary schools mostly focus on preparing students to take the University Entrance Exam [124]. In this exam, students must choose at least two subject areas related to the field that they wish to study at the higher education level. In preparation for these subject tests, students select their elective courses accordingly. Teachers follow the core curriculum, which is developed by the Mongolian Institute for Educational Research for these courses.

Students receive [13] the Certificate of Complete Secondary Education (CSE),29 [125] or Büren Dund Bolovsrolyn Ünemlekh (Бүрэн Дунд Боловсролын Үнэмлэх), or Gerchilgee (Гэрчилгээ) (“Certificate”). To earn it, students must pass the National Upper Secondary Examination.30 [126] This exit examination [109] consists of four parts:

- Mongolian language (including the traditional script) and literature

- Mathematics

- Choice of one of the following: biology, chemistry, geography, history, physics, or social science

- Choice of one foreign language: English or Russian

After receiving the CSE, students are eligible to take the University Entrance Exam and apply for higher education.

Vocational students who complete both their vocational studies (see the TVET section below) and the full upper secondary school track receive both a Vocational Certificate and the CSE.

The Education of Rural and Nomadic Children

Roughly 20 percent of the population of Mongolia are herders [127]. Most children of herders who do not live near a school are sent to a boarding school in the aimag center or soum center, where they stay most of the year except for during school breaks and in the summer.31 [128] Introduced in the socialist era, boarding schools were long considered a success because they significantly expanded access to education. However, in the mid-1990s, the government introduced fees for dormitory students, which resulted in a sharp drop in enrollment. Additionally, the move to lower the starting age of elementary school to age 6 in the mid- to late-2000s also caused enrollment drops [127], as fewer herder families wished to send their children to residential schools at such a young age.

In some cases, mothers move [127] with their school-age child (or children) to the soum or aimag center for the child to attend school, leaving the father and the rest of the family in the countryside. Studies suggest that this shift has led to an increase in divorce and prompted some families to abandon their traditional homes in the countryside to make new lives in soum or aimag centers or in Ulaanbaatar.

Educational outcomes of rural and nomadic children are generally poorer [127] than those of students in Ulaanbaatar and the aimag centers. For example, they perform less well on standardized tests and are more likely to drop out of school early.

The Mongolian government and some NGOs have introduced initiatives to improve education access and quality [127] for rural and nomadic children. These efforts have led to the construction of more dormitories, the introduction of traveling preschool teachers, improvements in the salary and working conditions of elementary school teachers in rural areas, and adjustments to the curriculum to make it more relevant for herders and farmers.

Large numbers of rural herders have migrated to major cities [127], notably Ulaanbaatar, due in large part to environmental factors, particularly droughts and dzuds, or harsh winters in which large numbers of herding animals typically die. Elevated levels of rural-to-urban migration have led to major overcrowding and high student-teacher ratios in many of Ulaanbaatar’s schools.

The Reverse Gender Gap

Mongolia is known for a pronounced reverse gender gap in education. After kindergarten and elementary school, girls and women outperform boys and men [59] at all levels of education. While enrollment rates for boys and girls are equally high in elementary school, the disparity between the two increases precipitously beginning in lower secondary school, where about 6 percent of boys are out of school, compared with only 2 percent of girls. This out-of-school rate grows to 14 percent of boys and 5 percent of girls in upper secondary school. In particular, boys from poor, rural, or farming or herding backgrounds are less likely to be enrolled in school. There is also a particularly big gender disparity in the eastern aimags.

These disparities continue after secondary school. At the higher education level, more women are enrolled than men. In 2018, the gross enrollment ratio for women in tertiary education was about 76 percent; for men, it was only 54 percent, according to data from the World Bank [129]. The effects are cumulative. In 2020, of the entire population age 25 and older, the post-secondary educational attainment rate for women was nearly half (about 46 percent), while for men it was only one-third (about 34 percent).

The reasons [130] for the underperformance of boys and men in education are complex, but sources often point to family obligations that boys may have—particularly in herder families where they must work—and to the lack of funding to send students to aimag centers or other larger communities to complete basic education. There are also complaints that the curriculum lacks relevance to herders. As a result of these factors, there is a higher drop-out rate among boys, particularly from rural and herder families.

While girls and women perform better in education, working-age women are underrepresented in the labor market overall. According to a report by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) [131], only about 53 percent of women were employed in 2019. This compares with about 68 percent of men. Women are also underpaid on average and relegated more often to jobs in less well-paying industries, such as social services, compared with men. Men continue [130] to hold most posts in government and the top leadership of companies across the country. Women are also typically responsible for the bulk of unpaid household and childcare duties [131]. The COVID-19 pandemic also forced more women to remain at home with their children when childcare was restricted to slow the spread of the virus.

Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET)

Technical and vocational education (TVET) and training in Mongolia [132] is guided by the Law on Vocational Education and Training, which was most recently revised in 2009. The sub-sector is in fact regulated by a blend of the government and the private sector through a body called the National Council on Vocational Education and Training (NCVET). The Ministry of Labor and Social Protection (MLSP) is the main government body in charge of TVET and is “responsible for coordination and implementation of TVET policy, strategy, and planning.” Among MLSP’s duties are the regulation of TVET training institutions, the development of occupational standards in conjunction with private industry, and the training of TVET teachers. MLSP also works in conjunction with [13] MES to regulate TVET institutions. Since 2002, TVET institutions have also been accredited by the Mongolian National Council for Education Accreditation (MNCEA).

According to UNESCO [132], four sources account for most of the TVET funding in Mongolia: the national budget, a levy on foreign workers, international development assistance, and private corporations. Of these, the national government provides the largest levels of funding.

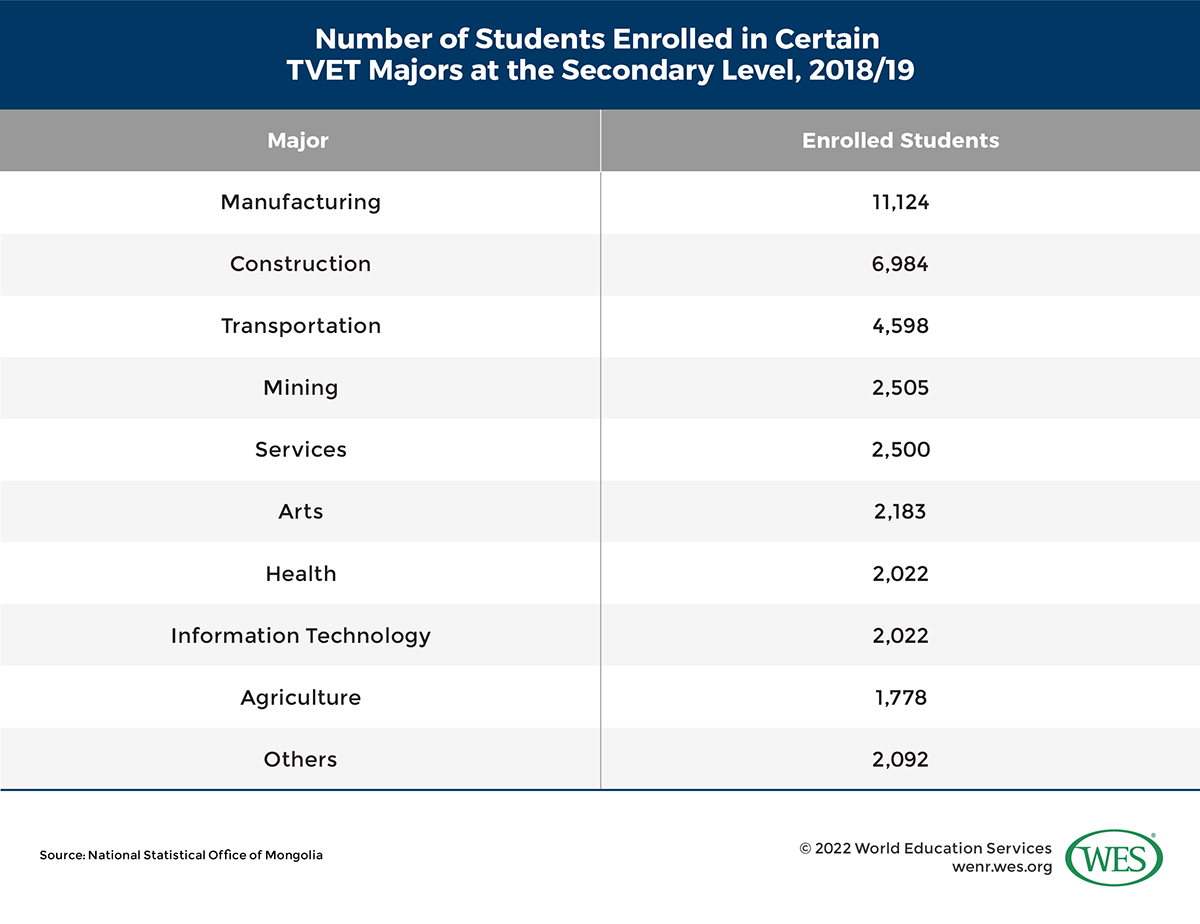

Secondary-Level TVET

Formal TVET [132] at the secondary level begins for students in 10th grade. The entrance requirement is to have completed lower secondary education; there is no admissions examination. Students can enroll in secondary-level TVET programs at Vocational Training and Production Centers [13] (VTPCs) or polytechnic colleges. Students major in fields such as agriculture, construction work, cosmetology, and hairdressing.

There are two main tracks [132] for formal TVET available to secondary school students:

- A one-year program aimed at certain professions that leads [133] to a Vocational Certificate, or Mergejliin Bolovsroliin ünemlekh (Мэргэжлийн боловсролын үнэмлэх), available at VTPCs or polytechnic colleges. This program is intended to prepare students for direct entry to the labor market after graduation.

- A two-and-a-half- to three-year program after which students receive both a Certificate of Complete Secondary Education (CSE) and a Vocational Certificate, available only at VTPCs. Students can apply for post-secondary vocational programs with this credential, particularly the shorter (one-and-a-half-year) program that leads to a Technical Education Diploma.

The number of TVET institutions [61] has increased significantly in recent years. In the 2010/11 academic year, there were 63 institutions. But by 2021, there were 80 institutions, an increase of 27 percent. Sixty-two percent are public, and 38 percent are private. While the number of TVET students declined between 2011 and 2017, enrollments increased again in the 2019/20 academic year, when they reached 37,800. Male students make up more than half of all students in these TVET programs. In 2019/20, 59 percent, 22,000, of all TVET students were male.

Post-secondary TVET

The main institutions providing post-secondary TVET [132] are higher vocational education colleges. A few universities and colleges offer TVET programs as well,32 [135] often through specialized training centers. There are two main programs [132]:

- A one-and-a-half-year Technical Education Diploma, often just called a Diplom (Диплом). Applicants must hold a Certificate of Complete Secondary Education in a vocational track to be admitted.

- A three-year Technical Education Diploma (Diplom/Диплом) for those with a Certificate of General Secondary Education in a general track.

Both programs prepare graduates to enter the labor market or continue their training at a higher level. Graduates of these programs can apply and be admitted to the second or third year of bachelor’s degree programs.

Short-Term TVET Programs

There are also a significant number of short-term programs [132] in certain in-demand fields such as auto repair and cooking. Lasting three months or less, these programs are not a part of Mongolia’s standard education framework. The credential [133] usually awarded for these programs is the Competency Certificate, or Chadamjiin gerchilgee (Чадамжийн гэрчилгээ).

Originally these programs were not directly regulated by MLSP and were offered by private entities and are thus typically considered “non-formal” programs. However, in 2018, MLSP began regulating these programs to ensure better quality. As of 2019, there were about 2,000 institutions offering these programs, 712 of which were formal TVET institutions.

Higher Education

During the socialist era, Mongolian higher education consisted of one large state university [13], the National University of Mongolia (NUM) (sometimes also called the Mongolian State University in English), founded in 1942. In 1983, the university was divided into several specialist colleges. During this period, institutions were generally run by a committee representing the Mongolian People’s Revolutionary Party (MPRP), along with the university director or president, who was appointed directly by the party.33 [136] Today, there are many separate public universities. These universities are mostly autonomous, hiring their own faculty and setting their own curricula.

The administration of higher education institutions largely falls under the purview of the MES—specifically its Department of Higher Education. However, several specialized higher education institutions have been founded and are now largely run by specific government ministries. For example, the National Defense University was founded by the Ministry of Defense, and its president is appointed and dismissed by the Minister of Defense.34 [137] Because this institution is under the direct control of another ministry, many MES regulations, such as those concerned with institutional leadership, do not apply.

Types of Institutions

As of early 2022, there were 76 accredited higher education institutions [86] in Mongolia, though UNESCO notes that there were 94 institutions in 2020 [13]. These institutions are both public and private [138] and are classified into the following types:

- Universities (ikh surguul (singular)/их сургууль) provide bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degree programs. Most degree programs include research, practical training, and laboratory courses or other forms of research experience. Some universities offer only master’s and doctoral programs. Universities are also expected to conduct research. There were 35 universities—14 public and 21 private—as of 2020 [13].

- Institutes (deed surguul (singular)/дээд сургууль) award bachelor’s and master’s degrees, primarily in scientific fields. They also conduct some research. There are 52 institutes: four public and 48 private.

- Colleges (kollej (singular)/коллеж) run education and vocational training programs that include classroom instruction and practical training that culminates in a diploma or bachelor’s degree. They are dedicated exclusively to teaching and are not expected to produce any research.35 [139] There are six colleges, all of which are private.

There are a total of [13] 18 public institutions—14 universities and four institutes. The majority of higher education students—about 90 percent—attend public institutions [59], which are generally considered to be the more elite institutions in the country. Most institutions are in Ulaanbaatar [13].

Many universities, particularly the larger, public ones, are expected to work toward achieving the status of “world-class research universities” and improve research capabilities [140] and output among their faculty, research staff, and students.

Enrollment Trends

During the socialist era, higher education enrollment was relatively modest. According to data from the World Bank [141], in 1985, the gross enrollment ratio (GER) for higher education was 24 percent, with a total of 46,946 students enrolled. Following the abrupt transition to a market economy in the early 1990s, overall enrollment numbers and the GER fell. By 1993, only 28,722 students were enrolled.

But beginning in the mid-1990s, enrollment in higher education picked up and began to grow dramatically. By 2000, the GER had risen to about 30 percent, or 74,025 students. Enrollment continued to rise steadily until 2015, when the GER peaked at 68 percent and total enrollment reached 179,540 students. Data after 2018 are uneven, but there appears to have been a slight decrease in enrollment in recent years.

Despite the government’s attempts to spread development evenly [59] across the country, most students still study in Ulaanbaatar. The government’s chief attempt to increase enrollments elsewhere has involved reducing the required score on the University Entrance Exam, although this move has raised concerns about reductions in quality and the reputations of institutions outside of Ulaanbaatar.

A 2019 report [61] from the National Statistical Office of Mongolia noted that the top majors among university students were medical sciences (22 percent), business (20 percent), engineering (17 percent), education (15 percent), and law (8 percent).

Financing

State funds are only a small portion of institutional finances [26], even among public institutions. The biggest sources [59] of financing for higher education institutions are private, including student tuition and fees, donations, research grants, and revenue generation activities. Student tuition is actually the biggest source of income for institutions, encompassing 92 percent of the revenue of public institutions.

Finances are the largest barrier [59] to higher education for low-income Mongolians, particularly for rural students moving to Ulaanbaatar for school. In addition to tuition, these students must contend with paying for living quarters and deal with a higher cost of living. Traditionally, many students who were unable to afford tuition on their own, as well as orphans and the disabled, could access grants and loans from the Education Loan Fund, but the number of students receiving such awards has decreased in recent years. Those who benefit most from state aid tend to be the children of civil servants, rather than low-income Mongolians.

Some students receive government grants, allowances, and tuition loans from the government to study both at Mongolian institutions and abroad. The Education Loan Fund [142] provides three different types of aid:

- Loans for students studying in Mongolian institutions at the bachelor’s, master’s, or doctoral level

- Loans for students studying abroad at all levels

- Grants for learners with disabilities or for those whose family members are disabled

Some students also receive financial assistance from social care services. Additionally, some members of parliament use discretionary funds to finance scholarships for select students.

Some private and non-governmental organizations also support students through grants and scholarships. Higher education institutions themselves have their own policies toward awarding financial assistance to students.

Accreditation

Higher education and TVET institutions are accredited by the Mongolian National Council for Education Accreditation (MNCEA) [143] (Bolovsrolyn Magadlan Itgemjlekh Ündesnii Zövlöl/Боловсролын магадлан итгэмжлэх үндэсний зөвлөл), an independent, statutory agency. Established in 1998, this body is charged with accrediting all higher education and TVET institutions.36 [144] In order to receive government funding and for students to receive financial aid from the government, an institution (public or private) must be accredited. Program accreditation, however, is not compulsory [145].

As of March 2022, MNCEA had accredited 76 public and private higher education institutions [86], 30 TVET institutions [146], and four secondary schools.

By regulation [147], MNCEA is governed by a board consisting of a “Chairman, Vice Chairman, and representatives from education institutions and professional communities.” Generally the chairman is an official from MES.

MNCEA itself is composed of several bodies [147]:

- The Secretariat is in charge of MNCEA’s daily operations.

- The Accreditation Commission for Higher Education is in charge of accrediting higher education institutions and all of their programs.

- The Accreditation Council for Vocational and Technical Education is in charge of accrediting all TVET institutions, such as polytechnical colleges and vocational schools.

- The Field Committees develop standards and provide accreditation for certain academic programs.

- External reviewers are the experts who conduct independent evaluations at the request of a council or field committee.

For institutional accreditation [148], there is a general three-step process:

- Self-evaluation: A team within the institution completes the self-assessment, ensuring that the institution meets MNCEA’s criteria. The evaluation is then reviewed and approved by the institution’s governing board. Once approved, the self-assessment is submitted to MNCEA.

- Review by external experts: If satisfied with the initial application, the Secretariat of MNCEA appoints a coordinator to review the self-assessment more thoroughly to ensure full completion. Once satisfied, the coordinator hands the assessment to the relevant internal commission (the Higher Education Commission or the TVET Commission), which assembles a team of experts to handle the process. The team of experts thoroughly reviews the self-assessment and then conducts a site visit lasting from three to five days, during which they gather information as needed. They then draft a report in which they recommend that the institution has “fully met,” “provisionally met,” or “not met” the standards for accreditation.

- Accreditation decision: The commission reviews and discusses the expert report. If satisfied with the experts’ opinion, they then agree to one of the following:

- Fully met: A proposal for five-year accreditation

- Provisionally met: A proposal for one- or two-year accreditation

- Not met: A statement, after which the process ends

The Governing Board then approves the decision. If accredited, the institution then begins the registration process. There is an appeals process for institutions that disagree with MNCEA’s final decision.

Program accreditation [148] follows the same basic steps. Instead of one of the two commissions, however, one of the field committees, which develop programmatic standards, conducts the review within MNCEA.

According to MNCEA [149], 17 Mongolian higher education institutions have achieved accreditation for at least some of their programs from international accreditation bodies. The main international accreditation bodies include:

- The Accreditation Agency for Study Programmes in Engineering, Informatics, Natural Sciences and Mathematics (ASIIN) [150], based in Düsseldorf, Germany: This agency accredits programs in “engineering, the natural sciences, mathematics, computer sciences as well as in medicine and economics” at bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral levels. It has provided accreditation [151] to 304 institutions in 44 countries. The Mongolian University of Science and Technology was the first institution [149] in the country to achieve accreditation from ASIIN in 2013.

- The Accreditation Council for Business Schools and Programs (ACBSP) [152], based in Overland Park, Kansas,United States : The organization accredits business schools worldwide. Its website lists 1,200 member institutions in 60 countries. It is recognized by the Council of Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA) [153], the main body providing quality assurance [154] to accreditation organizations based in the U.S. ACBSP has had a relationship with MNCEA [149] since 2008 and signed a formal memorandum of understanding in 2011. The Institute of Finance and Economics was the first Mongolian institution to begin the accreditation process with ACBSP in 2010.

- The Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology (ABET) [155], based in Baltimore, Maryland,United States: ABET accredits higher education programs in “applied and natural science, computing, engineering, and engineering technology at the associate, bachelor’s, and master’s degree levels.” The organization has accredited “4,361 programs at 850 colleges and universities in 41 countries.” A recognition summary from CHEA [156] notes, in 2019: “ABET with[drew] from CHEA recognition[.]” The reason for this withdrawal was not provided. According to MNCEA [149], ABET has accredited a total of three programs at two public universities. It is unclear when the organization began accreditation in Mongolia.

- The Accreditation, Certification and Quality Assurance Institute (ACQUIN) [157], based in Bayreuth, Germany: It focuses on accrediting bachelor’s and master’s degree programs in all fields, with a focus on Germany and the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) and was started in particular to accredit university programs in the German state of Bavaria. Priority regions [158] outside of Europe include Central Asia, North Africa, and Arabic-speaking countries. ACQUIN first began accrediting programs [149] in Mongolia in 2018, starting with four undergraduate programs.

A list of programs [159] accredited by one of these international agencies is available in English on MNCEA’s website.

Institutional Governance

At least in theory, all Mongolian higher education institutions are independent and can hire their own faculty and staff. Institutions have attempted to adopt the shared governance system [160], in which representatives of all major stakeholders from across the institution – such as administration, governing boards, faculty, staff, and students – are involved in policy- and decision-making. This model has been adopted from the U.S. and other Western countries, particularly under the influence of donor organizations. However, O. Gantogtokh37 [7] has argued that “the state-run universities haven’t achieved desired autonomy due to different ruling parties’ interests and short-term political reversals.”

By law, all institutions must have a governing board, such as a board of directors.38 [161] The government regulations on governing boards for both public and private institutions change frequently as the government changes. In general, however, boards are supposed to be the top level of governance for an institution, though this does not always happen in practice, particularly within private institutions. Boards have budgetary responsibility for the institution and are generally in charge of strategic planning, including in areas such as organization, staffing, salaries, and enrollment. In public institutions, boards are also generally supposed to recommend the appointment or dismissal of the executive leader of the institution (that is, the president or director). The appointment or dismissal is ultimately carried out by the MES or other relevant government ministries.

Governing boards at both public and private institutions are mandated to include representatives of the “founder” (that is, the government or a specific ministry, in the case of public institutions, or the proprietary owner of a private institution), faculty, students, and alumni.39 [162] There are few regulations about the actual proportional composition of the board, except that the founder’s representatives should represent 51 to 60 percent of board members. In public institutions, government officials usually represent a large percentage of board members, sometimes leading to concerns about institutional autonomy. These officials can come from MES, the central government, or a specific ministry, particularly for institutions with a specific focus or founded by a specific government ministry.

In the case of private institutions, founders often select a large number of individuals internal to the institution, such as members of the administration or faculty, according to an analysis by Jargalsaikhan.40 [163] Governing boards in these institutions are often, in the words of Gantogtokh, largely “symbolic,” with the owner making the majority of decisions for the institutions. That said, Jargalsaikhan’s analysis found that 14 private institutions consider their board of directors to be the highest authority within the institution.

The executive leader of a higher education institution can be called a president or director (zakhiral/захирал), or rector (rektor/ректор). In public universities, the board of directors is supposed to appoint the president, but in reality, the government (likely MES or another ministry) usually does.41 [164] Typically, in private institutions [145], the president is the proprietary owner of the institution or is appointed by the owner.

Faculty and Teaching Staff

All higher education faculty members are required to have at least a master’s degree [165]. The current regulations [165] also stipulate that 15 percent of faculty at institutes and 30 percent of faculty at universities should hold doctoral degrees. Master’s and doctoral degree programs may only be taught by faculty with doctoral degrees.

It is common for students at Mongolian higher education institutions to simply call professors or lecturers “Teacher” (Bagsh, or Bagshaa in direct address).

A 2020 MES order [166] specified general performance requirements for all faculty, which are divided into three areas: teaching, research and innovation, and professional and social service. Although the expectations differ according to the rank of the faculty member, faculty at all levels are expected to engage in all three areas.

University faculty are expected to participate in professional development activities, which are often provided directly at their institutions. Faculty at institutions outside of Ulaanbaatar sometimes go to the city for periodic training seminars and workshops. In some cases, trainers from Ulaanbaatar come to rural institutions to provide training. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many of these training opportunities were offered online.

Academic Calendar and Credit and Grading Systems

The academic calendar runs from September to June and is typically divided into two semesters.

Mongolian higher education institutions utilize a credit-hour system very similar to that used at U.S. [167] and Canadian [168] institutions. For example, most four-year bachelor’s degree programs in Mongolia require students to earn 120 credit hours to graduate, the same as for most American programs. (To convert these credits to the European Credit Transfer System (ECTS) [169], most recommend [170] doubling the number of credits in the U.S. or Canadian system to achieve the appropriate number of ECTS credits. A typical bachelor’s degree in ECTS [171] is 180 to 240 credits.)

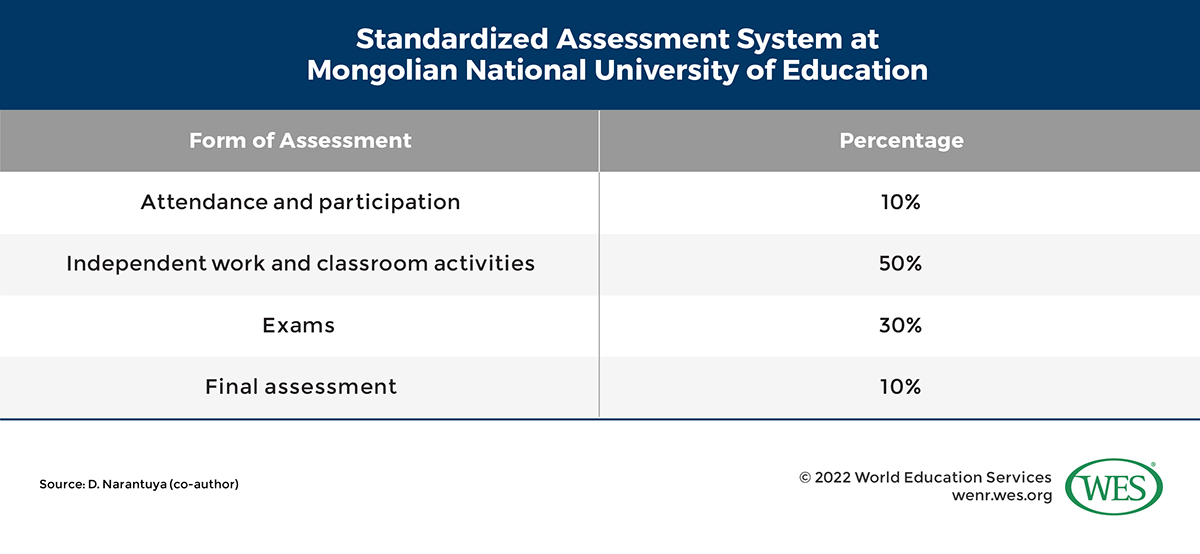

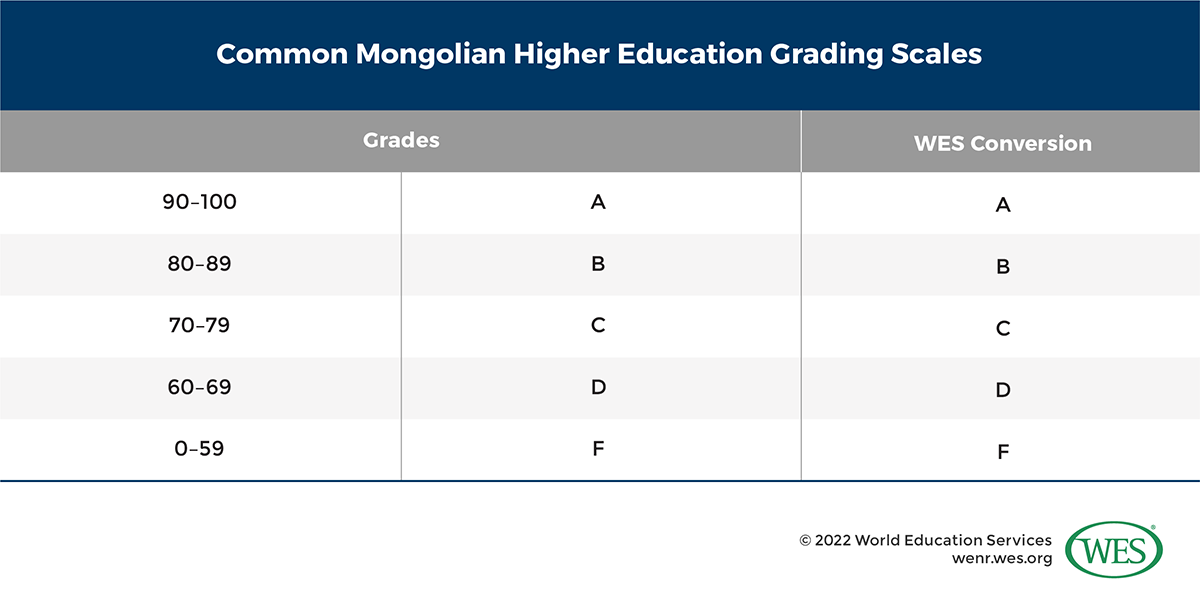

The grading system for most institutions is also closely aligned with those used in the U.S. and Canada, including a percentage and letter grades in the A to F scale and a 4.0 grade point average (GPA) scale. Assessment within individual classes can involve any mixture of examinations, projects, independent coursework, and attendance and participation. Grading systems can differ among institutions.

Below is WES’ grading conversion scale for Mongolia.

Undergraduate Education

To be admitted to an undergraduate program, students must hold a Certificate of Completed Secondary Education and take the University Entrance Exam (explained below).42 [174] Some private institutions also hold their own entrance exams.43 [175]

The main undergraduate degree offered in Mongolia is the bachelor’s degree (Bakalavryn zereg/Бакалаврын зэрэг), which is typically awarded after four years of full-time study and the completion of 120 credits.44 [176] Beginning in 2014 [94], bachelor’s degree programs began to follow the U.S.-style [167] liberal arts model: Students receive about one and a half years of general education (in a variety of subjects) and two and a half years of instruction in their major subject. Generally, students must achieve a final GPA of at least 1.7, or an overall grade of 61 percent or more, to earn this degree. Students may be required to complete a thesis, final project, internship, or some practical experience in order to be awarded the degree, depending on the institution and field of study. Some institutions, such as the National University of Mongolia (NUM) [177], recognize minor fields of study, similar to U.S. institutions.

In several fields, students earn their first professional degree at the undergraduate level.45 [178] Bachelor’s degrees in pharmacy and veterinary science are awarded after five years of full-time study. Bachelor’s-level medical and dental [179] degrees are each awarded after six years (see Medical Education).

Additionally, a much smaller number of institutions offer a diploma (Diplom/Диплом), which students can usually earn after two or three years of full-time study.46 [180] This has sometimes been compared with [181] an associate degree in the U.S. While the diploma is meant to grant students access to certain technical fields, graduates may receive up to two years of advanced standing in a bachelor’s degree program.